Fair warning: some (simplified) literary theory coming up. But all in the service of describing how Granthika works.

Granthika – of course – allows writers to create and manipulate text, but also enables writers to smoothly manage the structural components of their manuscripts (its chapters, sections, and scenes). Additionally – and crucially – it allows writers to treat the inhabitants and landscapes of the story represented by the text as closely-integrated components of their world-building.

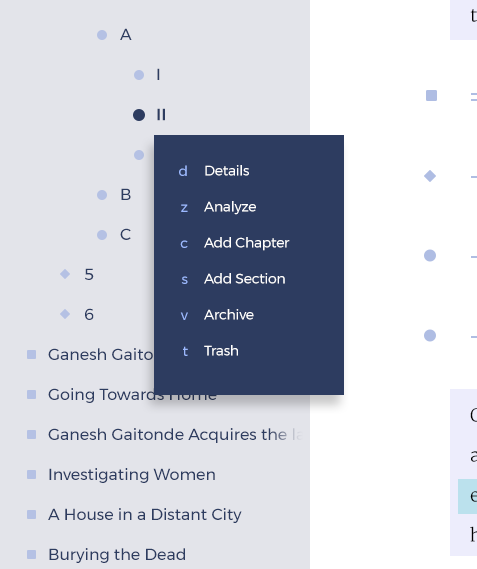

So, on the left of Granthika’s user interface, you see a “Table of Contents”:

The Table of Contents (TOC) represents the sequential structure of your manuscript. Granthika allows you to assemble your entire manuscript using the traditional building-blocks of written narrative: Parts, Chapters, Sections, and Scenes. As you might expect, a Part can contain several chapters, a Chapter can contain several sections or scenes. But none of this structure is forced on you – if you want, you don’t have to use parts at all, or structure your entire text using only chapters.

The “Scene” is the most granular element in Granthika’s repertoire. That is, a scene can contain only text, and have no sub-components.

Notice that in the image above, the user has right-clicked an element in the Table of Contents to bring up a contextual pop-up menu. This menu allows you to add meta-data (“Details”) at any level of the manuscript; you can indicate which characters participate in the action of a chapter, add notes about a scene, and so on. More about this to follow in future blog posts.

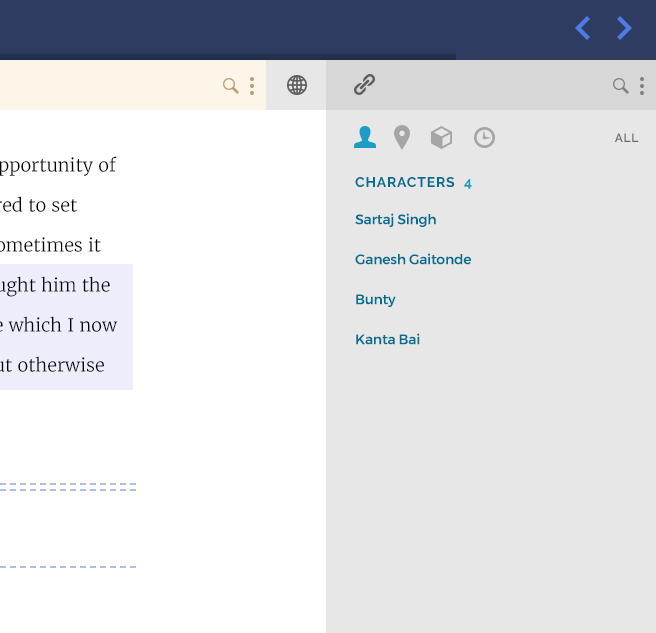

Now, on the right of Granthika’s user interface, you see what we’re calling the Connections Panel:

In the figure above, the writer is working on a particular scene, and in the connections panel you can see all the characters who are participants in that scene. Notice the other icons, which give you access to geographical locations, objects, and events related to that scene as well.

What this means is that the writer always has easy and instant access to all the elements of his or her universe. The elements in these lists – such as “Sartaj Singh” – will provide instant access to all the information (birth date, description, notes, etc.) that the writer has accumulated about these elements through the writing process. Relevant data is always a single mouse-click or keystroke away.

Literary theorists have provided useful ways of thinking about the relationship between a manuscript’s text and the people, locations, and events – fictional or otherwise – that the text describes. Seymour Chatman observes that any narrative has two aspects, “a story (histoire), the content or chain of events (actions, happenings), plus what may be called the existents (characters, items of setting); and a discourse (discours), that is, the expression, the means by which the content is communicated. In simple terms, the story is the what in a narrative that is depicted, discourse the how.”[1]

So the history (or histoire) of a narrative may be thought of as the what-actually-happened, as the content. It is quite different from the form of the narrative, its discourse (or discours); you could make two quite different narratives out of the same history by choosing different events to dramatize, or by changing the order of the scenes you then create, or by manipulating the mood of the scenes in your discourse. Think, for instance, of all the different novels and biographies written about the life of Mary, Queen of Scots – they may describe the same events, the same people, but each is quite different from the next.

Don’t worry – you don’t have to understand or even worry about any literary theory to use Granthika. But you may see us using a small amount of language borrowed from this body of theory in our user interface and documentation. For instance, we refer to manuscript parts, chapters, sections, and scenes as “discourse elements” (DEs). Characters, objects, and geographical locations are “existents.” We’ve used some of this theory as the underlying basis for Granthika’s handling of narrative (fictional narrative for now, but non-fiction as well in the near future). The end result is that while all this heady literary-nerd underpinning remains largely invisible to you – the author – it helps create a coherent, consistent user experience which every professional writer will immediately understand.

But if you’re interested in these notions of history and discourse, Seymour Chatman’s Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film is a splendid introduction. If you want to dive deeper, you won’t find a better survey of the field than Kent Puckett’s award-winning Narrative Theory: A Critical Introduction (full disclosure: Kent is a friend and a colleague of mine in the English department at Berkeley).

In our next post, we’ll show you some more about how Granthika integrates knowledge and text. Until then, may the birds sing outside your window as you work, and the writing flow.

Seymour Benjamin Chatman, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1978), 19. ↩︎

To download the latest version of Granthika, click here.